Drawing the Lewis structure for carbon dioxide (CO₂) may seem straightforward at first glance—but there’s more going on beneath that linear line than meets the eye. It’s not just about placing dots around atoms; it’s about uncovering molecular shape, bond character, and the subtle balance of electrons. Let’s wander through the process, chat about why things look the way they do, and toss in a bit of human unpredictability—because few things in chemistry are ever truly simple.

Understanding CO₂ Basics

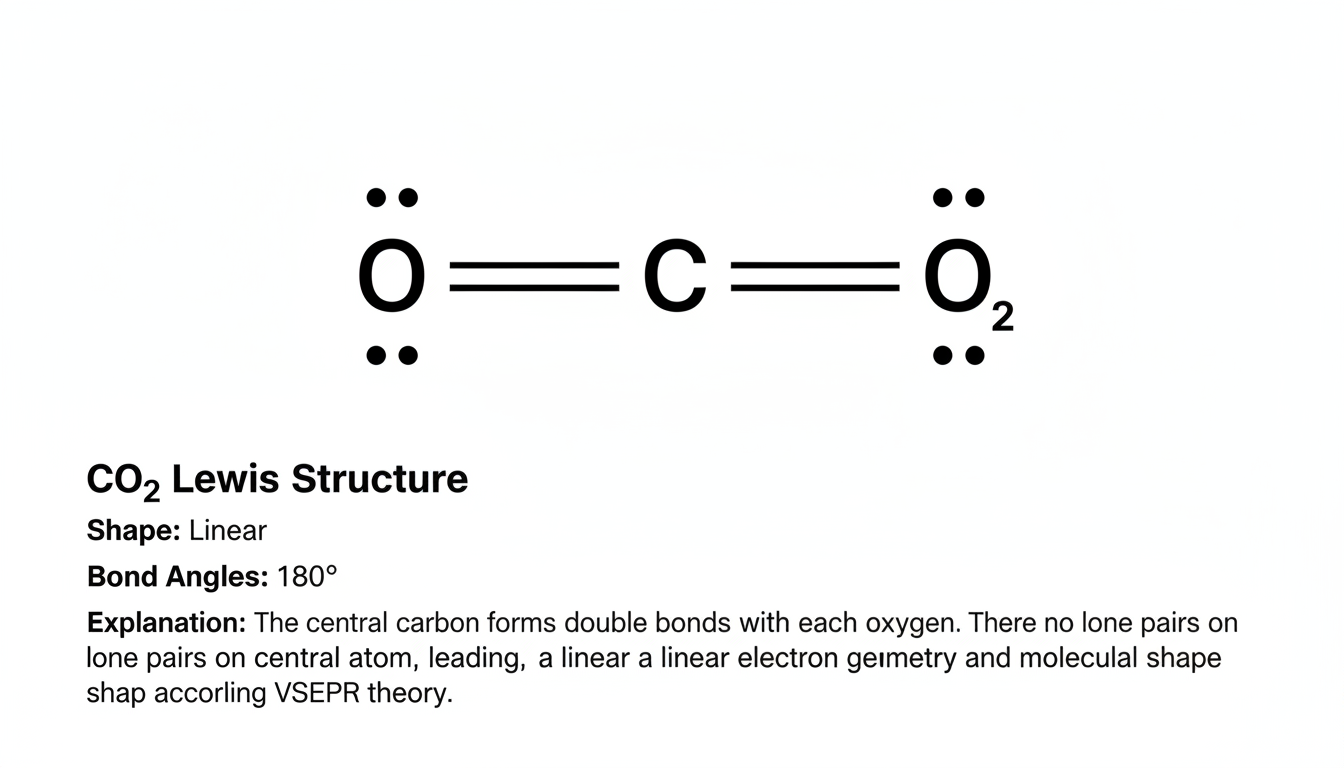

At a quick glance, CO₂ is a small molecule: one carbon atom double-bonded to two oxygen atoms. But here’s a little “aha” moment—carbon starts with four valence electrons, and oxygen brings six each. That’s 16 electrons total to arrange. The goal? Octet rule satisfaction for all participants, plus no charge if possible.

There’s a bit of trial-and-error here—like fitting puzzle pieces without forcing them. Some folks, me included, might start with single bonds and be surprised to find it doesn’t add up: each atom needs more electrons to reach eight. So the “duh” move is forming double bonds: C=O on both sides.

Constructing the CO₂ Lewis Structure

Step-by-Step Drawing

- Step 1: Count total valence electrons (4 from carbon + 12 from oxygen = 16)

- Step 2: Place carbon centrally—it’s less electronegative, so it’s usually the center.

- Step 3: Connect O–C–O with single bonds, which uses 4 electrons out of 16, leaving 12.

- Step 4: Distribute remaining electrons to fulfill octets for oxygen. But if you place them solely as lone pairs, carbon ends up thirsty for electrons.

- Step 5: Convert lone pairs into double bonds until carbon is saturated—this usually means two double bonds, one to each oxygen. That uses another 8 electrons, leaving none leftover.

By the end, every atom achieves an octet, and the structure is neutral. It’s like a dance of electrons, balancing around.

Common Slip-Ups

Some people forget to count electrons properly and stick with single bonds—they might end up with charges or incomplete octets. Others might overthink and add lone pairs to carbon unnecessarily. The double-bonded structure is the stable one, but it’s easy to land in a less stable resonance form if you’re not careful.

Molecular Shape and Geometry

Linear Structure and Bond Angle

CO₂ is definitively linear, with a bond angle of 180°. The two electron regions (the double bonds) repel each other evenly around the carbon, resulting in this flat, straight shape. It’s symmetrical and simple—yet elegant.

“The linear geometry of CO₂ is a perfect illustration of VSEPR theory in action—regions of electron density arrange themselves as far apart as possible,” as a chemist friend once explained during a casual pub discussion.

Because of that symmetry, there’s no net dipole moment even though the bonds are polar—carbon isn’t pulling more on one oxygen than the other overall. That’s why CO₂ behaves as a nonpolar molecule in many contexts.

Bond Characteristics and Real-World Implications

Bond Order and Electron Sharing

Each C=O bond is actually a combination of one sigma and one pi bond—classic characteristics of a double bond. Compared to a single bond, double bonds are stronger and shorter, which has consequences. For instance, CO₂ has a relatively high bond energy for such a small molecule—making it stable under normal conditions.

Atmospheric and Environmental Context

CO₂ might be “just a gas” in the lab, but in the real world it’s front and center in climate discussions. It’s a greenhouse gas, meaning its vibrational modes allow it to absorb and emit infrared radiation. Its linear geometry plays a role in how those vibrational modes interact with energy. On a silent evening, CO₂ is quietly doing chemistry that matters globally.

In industry, the strength of C=O bonds also means CO₂ is not easily broken apart—something chemists wrestle with when trying to convert it into useful fuels or chemicals. You can’t just zap it with energy; you need smart catalysts and carefully engineered steps.

Delving Into Resonance and Electronic Distribution

Resonance Forms? Sort Of.

Unlike something like ozone (O₃), CO₂ doesn’t exhibit classical resonance in terms of shifting double bonds—every workable depiction has double bonds at both ends. But you could draw less stable charged resonant forms (like one with a + and –), and those might pop up in discussions about reactivity or under unusual conditions.

Charge Distribution and Polarity

While there’s no net dipole overall (it’s nonpolar), the individual bonds are polarized—oxygen is tugging more, creating partial negative charges on the oxygens and a partial positive on carbon. That subtle charge distribution matters for how CO₂ interacts with metal catalysts or enzymes that try to fix carbon in nature (hello, photosynthesis).

Mini Case Study: CO₂ in Carbon Capture

In carbon capture efforts, chemists design materials—like metal-organic frameworks or amine-based solvents—that rely on how CO₂’s Lewis structure and polarity allow it to bind. Because CO₂ is nonpolar overall but still electron-withdrawing at the oxygens, it can form coordinate bonds or hydrogen bonds in these systems. The linear structure also means it fits snugly in certain porous materials.

While such capture systems aren’t perfect yet, they’re improving, and designs often reference that molecular geometry directly—proof that even a basic Lewis drawing has real-world resonance.

Why It Still Matters in Education

Many students groan about drawing CO₂ or understanding its structure, but it’s a staple example that reinforces fundamental concepts: electron counting, octet rule, molecular geometry, and polarity. It’s a backbone for organic and inorganic chemistry alike.

And honestly, teaching it can be a bit of theater. Explaining how eight electrons dance around, forming double bonds, and creating a linear shape—that’s chemistry storytelling at its most classic.

Conclusion

So, from the electron dot sketch to the real-world implications, CO₂’s Lewis structure bridges a simple textbook drawing and the weighty challenges of climate chemistry and materials science. Decoding it involves electron counting, geometry, bond order, polarity—all woven into one tidy molecule. It’s a vivid example of how foundational science quietly underpins global issues.

FAQs

How many valence electrons are in CO₂?

CO₂ has 16 total valence electrons—4 from carbon and 12 from both oxygens—used to form bonds and lone pairs that satisfy the octet rule.

Why is CO₂ linear in shape?

Because the electron regions (the double bonds to oxygens) repel each other equally around carbon, arranging at 180° for minimal repulsion, as described by VSEPR theory.

Is CO₂ polar or nonpolar?

CO₂ is overall nonpolar, thanks to its symmetrical linear geometry, even though each C=O bond is individually polar.

Why doesn’t CO₂ show resonance like other molecules?

CO₂ doesn’t have varying bond arrangements in its stable form—the double bond placements are fixed at both ends, so it lacks significant classical resonance.

How does the Lewis structure of CO₂ relate to climate science?

The molecule’s linear shape and electron distribution influence how it absorbs infrared radiation and interacts with capture materials—connecting its basic structure to environmental and industrial contexts.

February 6, 2026

February 6, 2026  6 Min

6 Min  No Comment

No Comment