In everyday math talk—and sometimes even in unexpected conversations—you’ll often hear about domain and range, especially when discussing functions. Think of these terms as the “what goes in” and “what comes out” of a mathematical process. They’re simple, yet surprisingly rich in nuance and quirks. Let’s walk through their real meaning, how they differ, and the crafty ways to find them—without making it sound like a robot.

What Are Domain and Range?

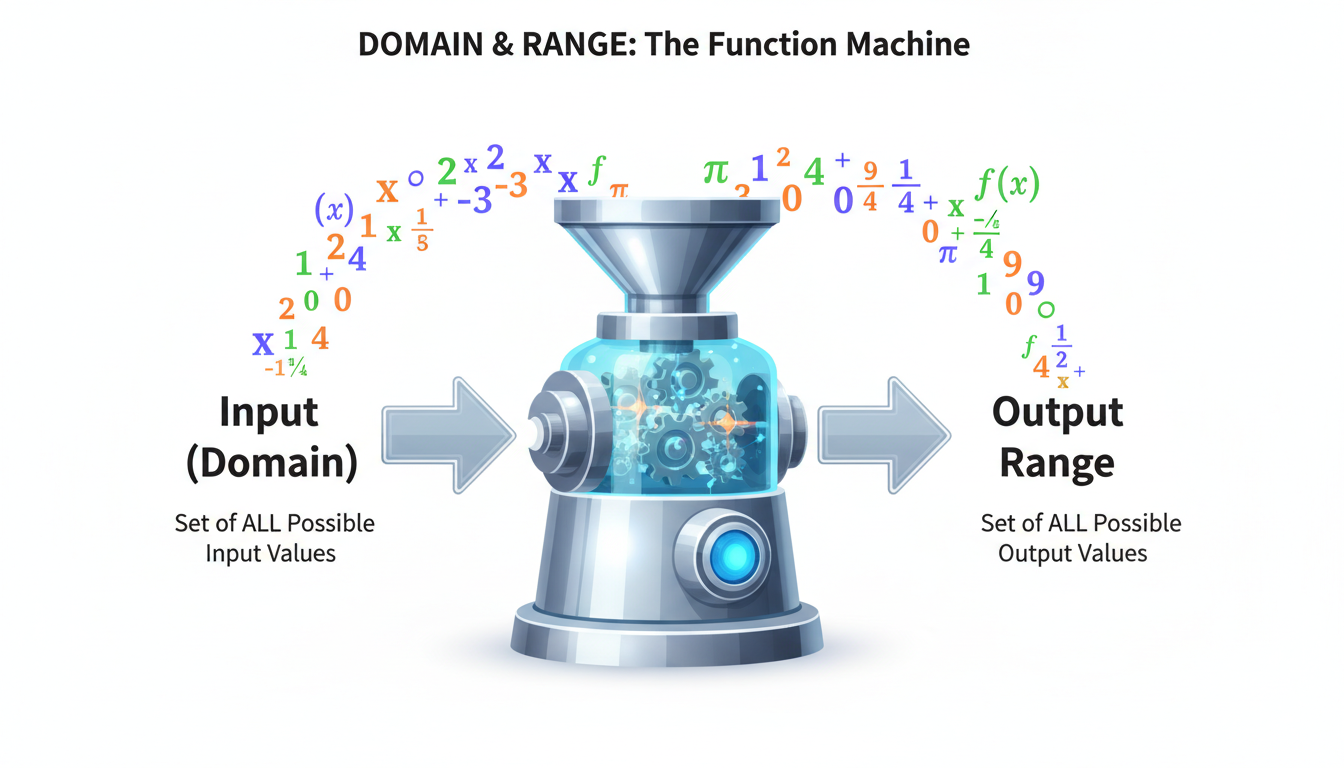

Grasping domain and range is like understanding the rules of a game: you need to know who’s allowed in and what comes out on the scoreboard.

Domain: The Legal Inputs

The domain is basically all the values you’re allowed to throw into a function without breaking it. In typical math classes, you’re told: plug in any real number, unless there’s something off like hitting a division by zero or a negative under a square root. For instance, (f(x) = \frac{1}{x}) can’t take (x = 0) because that’s undefined, so the domain excludes zero.

Range: What Comes Out

On the flip side, the range is the set of values that actually come out when you apply the function to each permissible input. It’s like everything that’s produced—every allowed output. Technically, this is called the image, but “range” often gets used broadly for both the image and co-domain.

Sometimes they match, but often they’re not the same—differentiating the two is key in advanced math.

Why Definitions Drift: Domain, Range, Co-domain

It’s not always that domain is an arbitrary set and range is what the function outputs. Actually, domain is a core part of the function’s definition: it tells you which set you’re starting from, often denoted as (f: X \to Y), where (X) is the domain. The co‑domain is what the outputs could exist in, while the range is what actually appears. If those two sets match, the function is called surjective.

Hence, though in many classrooms ‘range’ is used colloquially interchangeably with co‑domain, good practice is to reserve ‘range’ for the actual outputs (image).

How to Find Domain and Range in Practice

Here’s where things get fun (if you’re into math puzzles).

From the Formula

Several types of functions come with rules:

- Polynomials (e.g., (mx + b), (ax^2 + bx + c)): generally, no restrictions—domain is all real numbers.

- Rational (fractions): avoid dividing by zero by excluding those (x) values.

- Square Root: the expression inside must be non-negative, so solve ( \text{inside} \ge 0 ).

- Logarithmic: argument must be greater than zero, so domain is (x > 0).

Once the domain is nailed down, you often find range by analyzing the formula:

- Quadratics: complete the square or consider the direction of the parabola—this gives minimum or maximum (y) values.

- Rational: find horizontal asymptotes to spot values (y) cannot take.

From the Graph

Graphs are visual shortcuts: trace horizontally for the domain (all (x) the curve spans), vertically for the range (all (y) outputted). If the graph continues (has arrow tails), remember the domain or range might be unbounded.

Real-World-ish Example

Imagine a vending machine—you can only feed it quarters or dollars (domain), and it dispenses soda flavors, not burgers (range). This analogy highlights that domain and range define the set of possible and permissible inputs and outputs.

Examples That Make It Stick

Let me walk you through a few real examples:

( f(x) = x^2 – 4 )

- Domain: all real numbers (no restrictions).

- Range: since minimum value is (-4) when (x = 0), the range is (y \ge -4).

( g(x) = \frac{1}{x – 2} )

- Domain: (x \neq 2) (to avoid zero in denominator).

- Range: (y \neq 0), because the function never produces zero.

Square Root: ( h(x) = \sqrt{x + 3} )

- Domain: (x + 3 \ge 0 \Rightarrow x \ge -3).

- Range: outputs are always non-negative, i.e., (y \ge 0).

Logarithmic: ( \ln(x) )

- Domain: (x > 0).

- Range: all real numbers, since logs can produce any real output.

Trigonometric: ( \sin x )

- Domain: all real numbers.

- Range: between (-1) and (+1).

Expert Insight

“Understanding domain and range isn’t just memorizing lists—it’s appreciating the structure behind what inputs are valid and how outputs behave.”

This captures how these concepts reflect the nature of functions—not just numbers and symbols, but a guiding logic.

When Domain and Range Surprises Pop Up

Things get spicy when algebraic manipulation masks domain restrictions. For instance, ( f(x) = \frac{x^2 – 4}{x – 2} = x + 2 ) for all (x \neq 2). That simplification hides that (x = 2) is not allowed—even though the simplified form would say otherwise. That mismatch creates a “hole” at (x = 2)—a removable discontinuity—and the range then also can’t include the corresponding output (i.e., (4)). It’s a neat twist where domain and range differences become mathematically subtle.

Summary & Final Thoughts

Domain and range form the backbone of function understanding:

- Domain defines what you can plug into a function.

- Range captures what that function yields.

It’s not just formulaic rigmarole—these concepts show how functions behave, where they stumble (like dividing by zero), and what values they refuse to produce. Whether you analyze formulas or look at graphs, domain and range sharpen your mathematical intuition.

Understanding them thoroughly means fewer surprises when functions misbehave—and that feels great.

FAQs

What’s the difference between co‑domain and range?

The co‑domain is the set where outputs could land, by definition of the function. The range (or image) is the actual set of outputs produced. If they match, the function is surjective.

How do you find the range if you only know the domain?

Use the function’s formula: analyze its behavior (e.g., look for minimum/maximum values, asymptotes, sign), or examine a graph. Pages usually apply transformations or complete the square to pin it down.

Can domain and range ever be the same set?

Yes—consider the cube root function (f(x) = \sqrt[3]{x}). It accepts all real numbers and outputs all real numbers, so domain and range are both ℝ.

Why is (x = 2) excluded from the function ( (x^2 – 4)/(x – 2) ) even though algebraic simplification gives (x + 2)?

Because the original function has (x = 2) in the denominator, making it undefined there. Simplifying the expression doesn’t change that underlying restriction—resulting in a hole at that point.

February 6, 2026

February 6, 2026  6 Min

6 Min  No Comment

No Comment