Ever played with a soda can and wondered how much wrapping paper it would take to cover it completely—or even just the sides? That curiosity actually leads us straight into the deceptively simple—but surprisingly versatile—world of the total surface area (TSA) of a cylinder. And yeah, maybe sometimes the explanation from trusty ol’ textbooks read so perfectly that it feels too neat—like everything is in place. Reality, as usual, is a little messier, and that’s okay. Coming right up: the formula, the real-world bits, a couple of mini stories, and yes, a dash of human imperfection just to keep things relatable.

Understanding the Formula: TSA of Cylinder Demystified

The Basic Formula and What It Means

At its core, TSA of a cylinder sums up two parts:

– the curved (or lateral) surface area, and

– the two circular ends (the bases).

The formula you’ll see most often is:

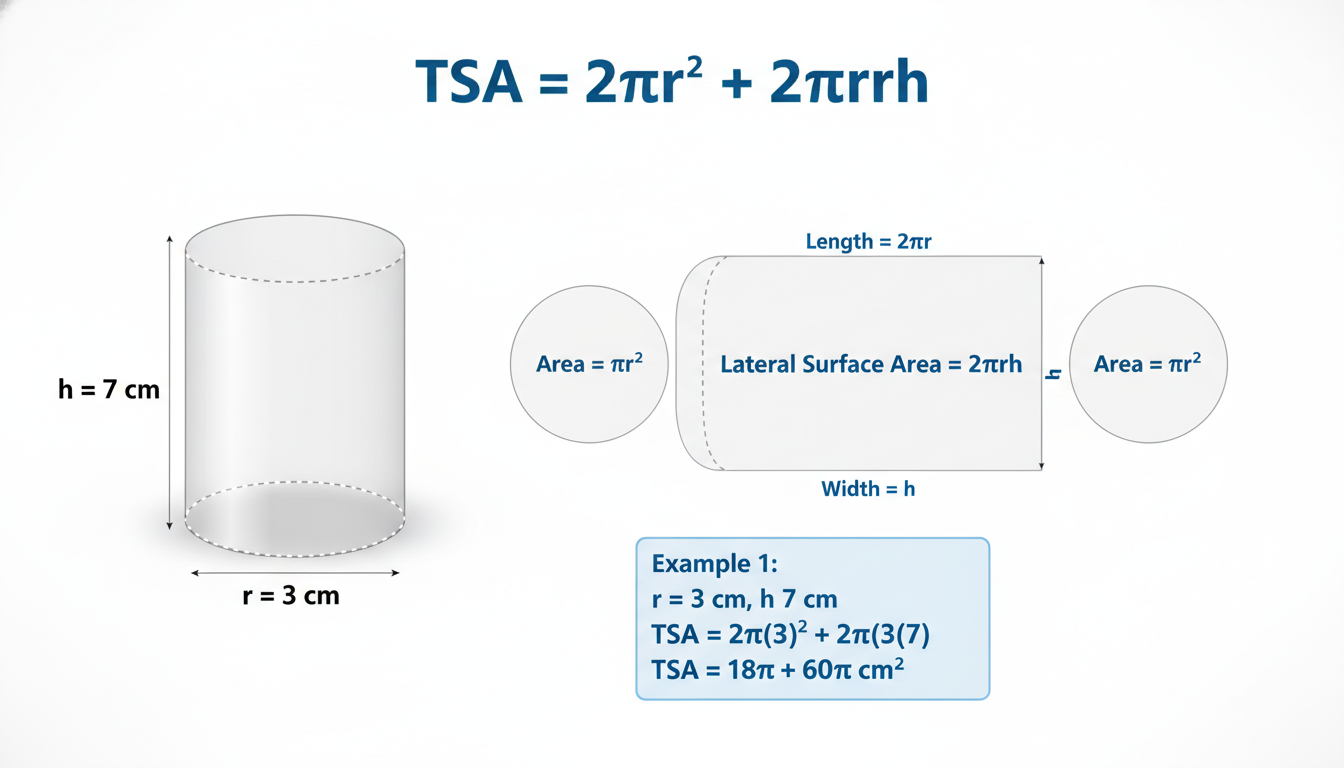

TSA = 2πr² + 2πrh, which can also be elegantly rewritten as 2πr(r + h) .

– 2πr² covers both circular bases.

– 2πrh gives you the curved surface area, which is like unwrapping the side into a rectangle whose width is the height (h) and length is the circumference (2πr).

A Visual Breakdown (But a Little Messier in Real Life)

Imagine slicing off both ends of a soup can and then cutting down the side and laying that curved bit flat. Boom—you get a rectangle (height = h, width = 2πr) plus two circles. That’s your components right there. In reality, cans don’t always peel off so cleanly, and sometimes the edges overlap, but the math holds—just like real packaging engineers know .

“In practical design—say for packaging or industrial tanks—we often rely on the 2πr(r + h) formula to estimate material needs or heat transfer surfaces, but allowances for seams, margins, or coatings always come into play.”

That little quote—something an engineer friend once muttered at 3 a.m.—captures how textbook formulas meet real-world tweaks.

Applying TSA in Real-World Scenarios

From Soda Cans to Monumental Tanks

Let’s talk real-world examples:

-

Soda cans, perhaps the classic: If a can has a radius of 3 cm and a height of 12 cm:

TSA ≈ 2π × 3(3 + 12) ≈ 2π × 3 × 15 ≈ 90π ≈ around 283 cm². Keeps your designer friends happy when they want to add cool graphics. -

Water tanks or industrial silos: Just scale the numbers—if the radius is 1 m, height is 5 m, TSA = 2π × 1(1 + 5) ≈ 12π ≈ ~37.7 m². That shapes cost estimates for coatings or insulation.

Textbooks from GeeksforGeeks or Cuemath show those kinds of examples and walk you through each calculation step .

Quick Tricks When You’re Given Diameter Instead of Radius

Sometimes, the problem gives a diameter (d) not a radius (r). Here’s a shortcut:

- Curved surface area (CSA) becomes: π × d × h.

- Total surface area becomes: πdh + (πd²)/2 .

Especially handy if the diameter’s used everywhere in the factory blueprints.

Practical Steps and Tips in Everyday Calculation

Step-by-Step

- Identify dimensions: Capture r or d, and h.

- Pick the right formula:

- TSA = 2πr(r + h)

- Or, TSA = πdh + (πd²)/2 if using diameter.

- Calculate each part:

- compute 2πrh for the curved area,

- compute 2πr² for the bases,

- then add them (or use the combined form).

Common Pitfalls and Imperfect Moments

- Overlooking both bases: If someone forgets the ‘2’ in 2πr², you’ll get just the curved part—oops.

- Radius vs. diameter mix-ups: Happens all the time in fast-paced labs and classrooms. Always check.

- Unit mismatch: Converting cm to m midway inadvertently? Yep, leads to messy answers if not careful.

Why Knowing TSA Really Matters

Beyond the Math—Into Design, Physics, and Beyond

- In engineering, TSA determines how much paint, insulation, or plating is needed.

- In physics, it’s vital for calculating heat loss or gain—think pipes or reactors.

- In 3D modeling, accurate TSA improves texture mapping and surface rendering.

So whether you’re designing rocket fairings or school projects, it matters.

Conclusion: Wrapping Up TSA with a Human Bolt

The total surface area of a cylinder isn’t just a textbook formula—it’s a real-life tool, a handy assistant in design, packaging, and engineering. Sure, the math is clean—2πr(r + h)—but real problems have seams, jagged edges, and mental oopsies. Embrace the imperfections, keep dimension-oriented, and let the cylinder shape guide what you need to calculate.

FAQs

What exactly does TSA of a cylinder include?

TSA covers the entire outside surface—the wraparound side plus both circular ends. In formula form, it’s the curved surface area (2πrh) plus the two bases (2πr²).

How do I handle TSA if only diameter is given?

Use the formula πdh + (πd²)/2—it’s derived from replacing r with d/2 in the standard formula, saving you a calculation step.

When would I only use curved surface area (CSA)?

If you only need to cover the side of the cylinder—like labeling or wrapping—it’s just CSA, which is 2πrh, without the top and bottom.

What errors should I watch out for?

Common pitfalls are mixing up radius and diameter, forgetting to multiply the base area by two, or mismatching units (e.g., cm versus m). Always double-check dimensions before plugging in.

Why choose the combined form (2πr(r + h)) over separate terms?

It’s cleaner and less prone to omission—one formula covers both parts. Just make sure both r and h are clearly defined.

Is TSA important outside of geometry class?

Absolutely. Engineers, designers, physicists, even graphic artists use TSA in daily work. It guides material estimates, thermal calculations, and accurate modeling—so it’s more than just classroom pap.

February 8, 2026

February 8, 2026  5 Min

5 Min  No Comment

No Comment