The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus is one of those mathematical gems that, when you truly grasp it, feels like uncovering a hidden shortcut—suddenly everything’s connected. It links the concept of differentiation with area under curves in a way that’s both elegant and profoundly useful. From physics and engineering to economics and data science, nearly every field that deals with change leans on this theorem in some fashion. And, well, while many of us recall a tidy definition from school, the real insight happens when you see how it plays out in actual problems, with examples and yes, even little mistakes that help you understand more deeply.

Understanding the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus: Breaking It Down

It’s surprisingly common to stitch together two separate ideas—differentiation and integration—and not immediately see how they fold into each other. There are really two key parts here:

Part I: Connecting the Integral to Accumulation

This first part tells us that if you take an integral of a function and treat its variable as something that changes, you get a new function whose derivative matches your original function. In plain-ish terms: when you define ( F(x) = \int_a^x f(t)\,dt ), then ( F'(x) = f(x) ). This notion—that the act of accumulating (through integration) unwinds via differentiation—is almost surreal when first encountered.

A quick scenario: imagine a water tank filling up at a rate ( f(t) ). The volume by time ( x ) is ( F(x) ). Then, your rate of change of volume at any given moment is exactly the filling rate—like you’ve reverse-engineered the process. That’s Part I in action.

Part II: Using Integration to Recover Net Change

Part II is often what people think of as “the Fundamental Theorem”—it allows you to calculate definite integrals via antiderivatives. Specifically, if ( F ) is an antiderivative of ( f ), then

[

\int_{a}^{b} f(x)\,dx = F(b) – F(a).

]

That means, rather than doing lumpy Riemann sums, you can use a simpler “plug-and-play” approach: find an antiderivative, then evaluate at endpoints and subtract. In real-world terms: to figure out total distance traveled, you find an antiderivative of your velocity, plug in start and end times, subtract, and—bam!—there’s the distance.

Bringing the Theory to Life with Examples

Let’s crystallize this with some more tangible scenarios:

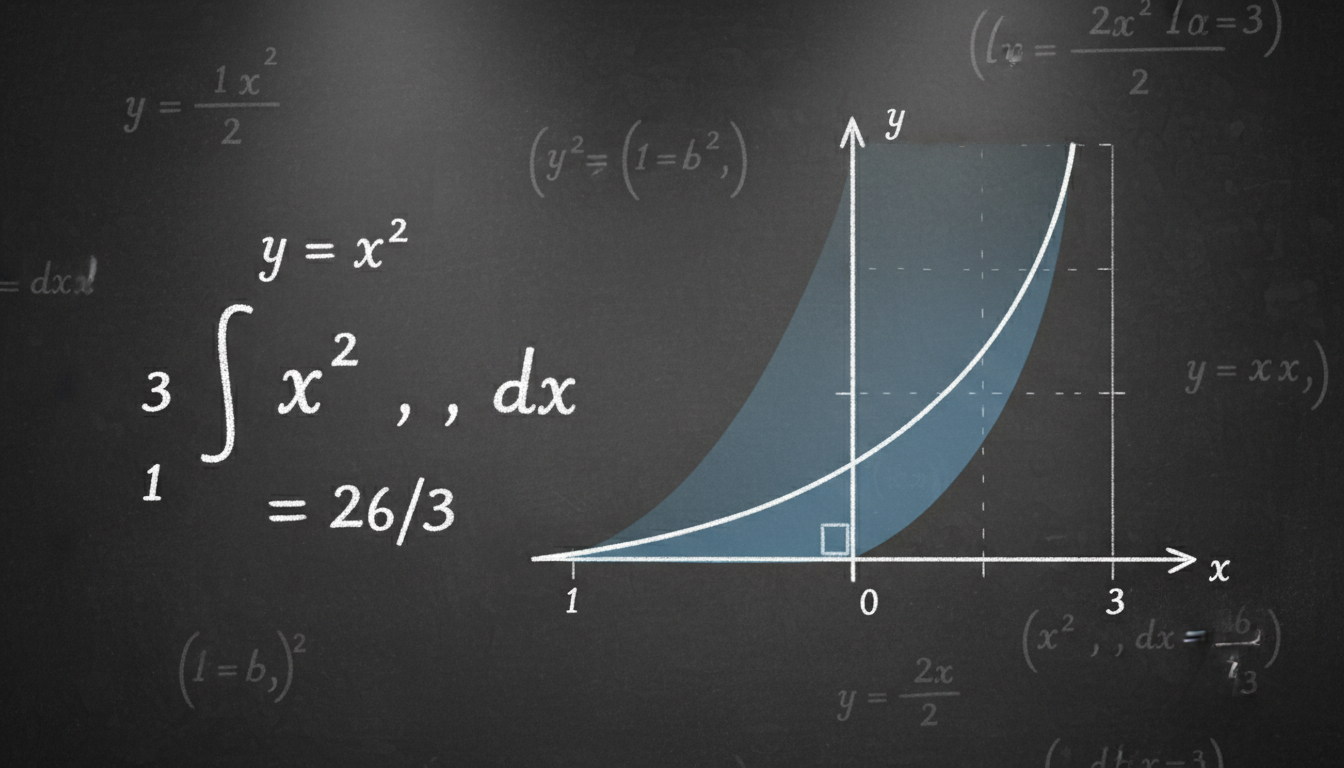

Example 1: Simple Polynomial

Take ( f(x) = 3x^2 ). An antiderivative is ( F(x) = x^3 ). So:

[

\int_{1}^{4} 3x^2\,dx = x^3 \Big|_{1}^{4} = 4^3 – 1^3 = 64 – 1 = 63.

]

This is Part II in action, and I still double-check whether I need to worry about constants of integration—though with definite integrals, those cancel out, which is kinda neat.

Example 2: Real-World Rates

Suppose a car speeds along at ( v(t) = 2t ) miles per hour after ( t ) hours. The antiderivative is ( s(t) = t^2 ). Want distance from ( t=3 ) to ( t=5 )?

[

s(5) – s(3) = 25 – 9 = 16\, \text{miles}.

]

Again, differentiation of distance gives you velocity, and integration of velocity gives you net distance—beautiful synergy.

Example 3: Sine and Cosine Crossroads

If ( f(x) = \cos(x) ), an antiderivative is ( F(x) = \sin(x) ). Then,

[

\int_{0}^{\pi/2} \cos(x)\,dx = \sin(x) \Big|_{0}^{\pi/2} = 1 – 0 = 1.

]

This is not just a math exercise—it represents things like horizontal displacement in wave motion, or even probabilities under normal approximation curves in stats, if you’re a bit more adventurous.

Common Misunderstandings and What Trips People Up

Often, people mix up which part does what, or misplace constants—and it’s totally human. A few stumbling points:

- Confusing indefinite integrals (antiderivatives plus a constant) with definite integrals—forgetting that the constant disappears in definite calculations.

- Assuming every function has an elementary antiderivative—spoiler: many don’t, like ( e^{-x^2} ).

- Thinking you can apply Part II without verifying continuity or other preconditions—your integrand needs to be nice enough (e.g., continuous on [a, b]) to ensure the theorem holds.

Precisely speaking, Part I requires ( f ) to be integrable and continuous at that point, while Part II generally needs continuity on the interval. Practically, most textbook examples satisfy those, but encountering exceptions can throw you off.

Why It Matters: Real-World Use Cases

Beyond homework, this theorem is the backbone for much of applied science:

- In physics, linking displacement, velocity, and acceleration is rooted in this theorem. Without it, predicting movement becomes awkward.

- Economics relies on integrating marginal cost or utility to understand total cost or benefit—priceless when modeling investments or consumer behavior.

- In data science, the principles underlining areas and slopes inform optimization algorithms and understand continuous distributions.

“Bridging differentiation and integration isn’t just math—it’s the logic that binds how we model and understand change across almost every domain.”

This isn’t just abstract; it’s a conceptual tool that empowers insights in simulation, forecasting, and more.

Clarifying Subtle Details

Sometimes the theorem is stated in slightly different ways—context matters:

The Continuity Caveat

The function ( f ) must be continuous on [a, b] for Part II to apply smoothly. If ( f ) jumps or misbehaves, you need piecewise integration or more advanced theorems. That continuous assumption is there for a reason—break it, and the usual procedure may fail.

Antiderivative Ambiguities

Since any antiderivative is correct up to a constant, when computing definite integrals, that constant cancels out. It’s a subtle detail that’s easy to forget, especially when switching back and forth between indefinite and definite thinking.

Putting It All Together: A Mini Case Study

Imagine a startup tracks user engagement growth rate ( u'(t) ) over time. To find total new users between Monday and Friday, they integrate ( u'(t) ). But to do that, they either:

- Find an antiderivative ( u(t) ) and apply Part II,

- Or use numerical methods or approximations if there’s no neat formula.

Seeing the inefficiencies when a function doesn’t behave nicely, they often smooth data or approximate so they can use the theorem, rather than churn through raw sums. That strategic adaptation reveals the theorem’s practical flexibility.

Concluding Summary

Understanding the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus is more than memorizing a formula—it’s about appreciating how differentiation and integration mirror each other. Part I shows that the process of accumulation (integral) reverses via differentiation, while Part II gives a powerful shortcut to calculate totals. Real-world examples—like motion, economics, or growth metrics—highlight how essential it is. Embracing the subtle conditions and interpretations avoids mistakes and unlocks deeper intuition.

FAQs

What is the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus in simple terms?

It states that integration and differentiation are inverse processes. Part I shows that the derivative of an integral returns the original function, and Part II lets you compute definite integrals via antiderivatives.

Can the theorem be used if the function isn’t continuous?

Generally, continuity on the interval is assumed for a safe application. If the function has jump discontinuities, you might need piecewise methods or more advanced integration techniques.

Why does the constant of integration disappear in definite integrals?

When evaluating an antiderivative at two points and subtracting, any added constant cancels out, so it doesn’t affect the result.

What’s a real-world example of this theorem in action?

One example is calculating distance traveled when given velocity. By integrating velocity (Part II), you get total distance; and the derivative of distance gives back velocity (Part I).

How do you handle functions without elementary antiderivatives?

In such cases, numerical methods like Simpson’s rule or approximation techniques are used. Alternatively, functions can be approximated or smoothed to enable practical application of the theorem.

Is the theorem relevant outside calculus classes?

Absolutely. It underpins models in physics, economics, data science, and engineering—anywhere change over time or accumulated quantities are involved.

February 8, 2026

February 8, 2026  7 Min

7 Min  No Comment

No Comment